Blog Post

Towards a cultural reset in restoring Africa’s drylands

Insights for empowering community-led land management as the UN Decade for Ecosystem Restoration (2021–2030) kicks off

by Wangu Mwangi and Jes Weigelt | 26 May 2021

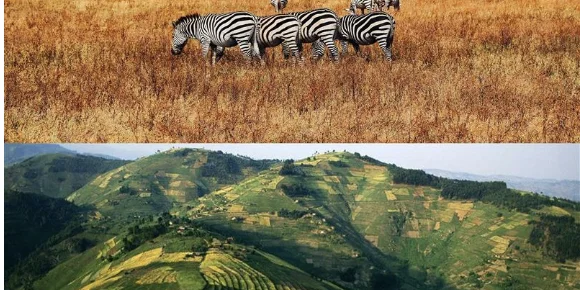

One of the most iconic images of Africa in international media is of vast rangelands teeming with wildlife. The dream of seeing “the big five” in the flesh not only fuels a multi-billion dollar tourism industry, but also draws in huge money for conservation programmes that promise to maintain Africa’s rich biodiversity as the last bastion of a rapidly disappearing natural world.

But there is also a downside to this romanticised view of the continent. People tend to be conspicuously absent from most of the glossy images. Or if they are, they are portrayed in colourful traditional costumes to complement the exotic locations that match the popular imagination. It is therefore not surprising that Africa’s beautiful landscapes are often the target of large-scale conservation efforts, both by public and private funders.

Different faces of Africa: Source: Jorge Tung on Unsplash and CIFOR

Why conservation approaches can lead to disempowerment

Unfortunately, such initiatives tend to focus on protecting “pristine” ecosystems by fencing them off and criminalising the use of natural resources by local communities. Across the continent, there are numerous accounts of the serious human rights violations that occur as a result. While widespread criticism of such approaches in recent decades has led to efforts to incorporate local communities in conservation efforts, in reality such support is often limited to token measures. These include food-for-work schemes, or one-off investments in social services such as schools or clinics without tackling the deep-rooted drivers of natural resource degradation. In many cases, such investments merely serve as a band aid to cover the very real impacts of increased conflicts over resources that may be fuelled by the very same conservation efforts.

Another inherent risk in top-down conservation measures is “elite capture” — both by local power holders as well as conservation projects. An example is Kenya’s Laikipia region, where thousands of hectares of land have been converted into private conservancies, ranches, and related tourism ventures, forcing pastoralist communities into ever-smaller limited areas. The resulting conflicts are a stark reminder of the dangers of conservation approaches that ultimately disempower the very communities that have sustainably managed such resources for centuries. It leads to a situation where small-scale farmers and pastoralists are accused of using land unsustainably, without addressing the underlying power dynamics that contribute to growing inequality and poverty for local populations.

Beyond rhetoric: scaling up people-based conservation and restoration

“Perhaps roughly ten percent of the planet remains an unpeopled “grand treasure” suitable for the set-the-land-aside approach, but how do we protect the remaining ninety percent? [Future.org]

Good practices in people-based conservation and restoration are well documented. The now classic study of land management practices in the populous Machakos district of eastern Kenya, famously titled “More people, less erosion” demonstrated that, with the right support, smallholder farmers can sustainably manage soil and other natural resources, while earning a decent livelihood. More recent research on afforestation in Southern Ethiopia concluded on a similar note, “more people, more trees.” Likewise, the Regreening Africa project has aptly demonstrated that it is farmers who can halt land degradation. While these examples are eclectic, the message is clear: given the necessary enabling conditions, smallholder farmers have the capacity to drive dryland restoration.

Renewed global interest in dryland restoration is also drawing serious money for this cause. A French-led international drive recently led to pledges of more than 14 billion dollars for the Great Green Wall Initiative, which aims to create a major green belt across Africa’s Sahel region. While the introduction of technology and funding can help speed up restoration, there are also inherent risks in a technocratic, and rushed approach to scale up local efforts. Global mobilisations of this type need to build on the efforts of local communities who have so far created an impressive green pastiche across this same zone, often with no external funding, and building on traditional knowledge and resilient indigenous seed varieties.

In order to ensure that restoration efforts contribute both to sustaining biodiversity as well as people’s livelihoods, it is essential to address governance gaps that could leave the door open to the “greenwashing” of conservation initiatives by both local, as well as external interests. This means that the UN Decade would need to focus attention on strengthening “the missing middle” between global and national restoration pledges on one hand, and local implementation capacities on the other.

Building on discussions at the 2019 Global Soil Week, the TMG Guide on creating an enabling environment for community-driven investments for the UN Decade further cautions that upscaling local restoration efforts is not equivalent to pouring ever greater resources into more pilot projects. Rather, it is critical to tackle the required enabling environment for people-centred restoration. Examples include: exploring innovative, cost-effective, and community-endorsed efforts to secure women’s rights to land; closing capacity gaps in technical infrastructure, especially at the sub-national level; and building inclusive extension services that link traditional knowledge to context-relevant scientific research.

How can GLF Africa catalyse bottom-up restoration efforts?

With its broad global constituency, especially among young people, the Landscapes Forum is an important mobilisation platform for accelerating the achievement of restoration targets. As the first-ever Digital Conference focused on Africa’s drylands, the GLF can use its convening power to shift the discourse from “counting hectares and trees” to “restoration by and for the people.”

But this requires exploring the much more difficult, but sorely needed, social (and political) innovations that can tackle structural impediments to scaling up restoration. In order to broach these more sensitive issues, the GLF platform will need to build on the assembled collective wisdom to not only address technological and financial fixes, but also propose concrete pathways, as well as strategic alliances that can take on the difficult questions of land rights and inclusion in African restoration agendas.

The GLF Africa Digital Conference will take place on 2–3 June 2021, just ahead of World Environment Day, and the official launch of the UN Decade for Ecosystem. TMG-Think Tank for Sustainability and its partners will convene a GLF Africa session titled ‘From Community-led Restoration to Carbon-Enhancing Landscapes’ on 2 June.

TMG Think Tank for Sustainability consists of TMG Research gGmbH, an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit organisation registered in Berlin (District Court Charlottenburg, HRB 186018 B, USt.-ID: DE311653675) and TMG - Töpfer Müller Gaßner GmbH, a private company registered in Berlin (District Court Charlottenburg, HRB 186018 Bm USt.-ID: DE311653675).

Our main address is EUREF Campus 6-9, 10829 Berlin, Germany.

Our main address is EUREF Campus 6-9, 10829 Berlin, Germany.